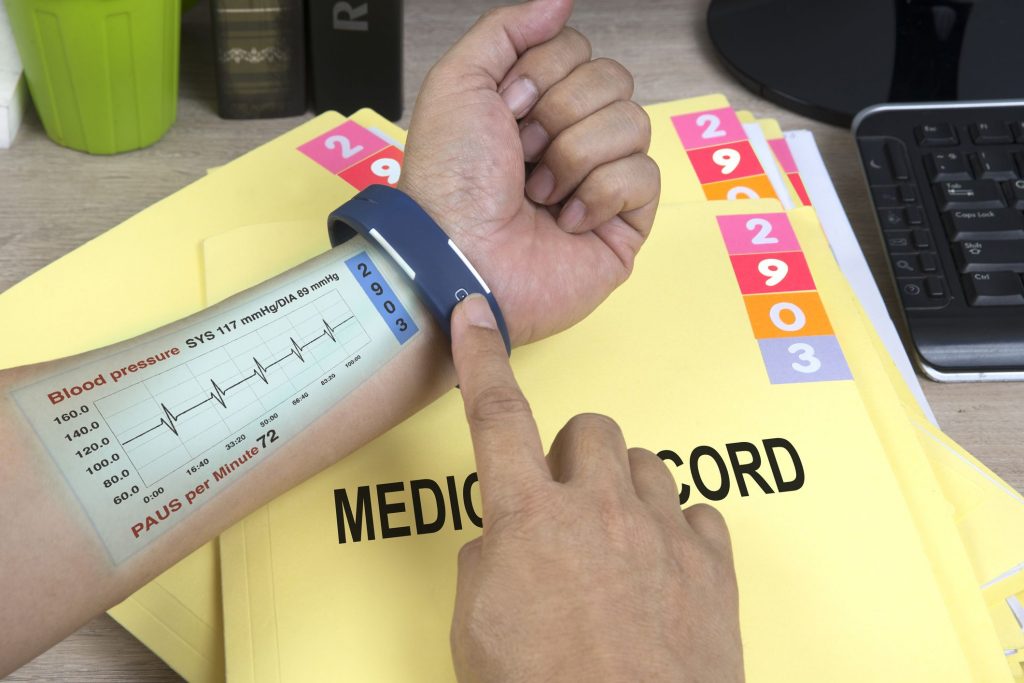

Since its May 2013 debut, the activity-tracking device Fitbit has been the go-to fashion accessory on the wrists of health conscious people.

The fitness accessory is one of the most visible and well known examples of wearable health technology, a broad category that includes products performing functions from counting the number of steps a user takes in a day to detecting heart arrhythmia and potentially preventing a heart attack.

It’s a booming market, projected to grow to $27.8 billion by 2022, according to a 2016 study from Grand View Research.

Advances in technology, such as wireless wearable biosensors and 3D printing are important to the expansion of this sector. The growth of wearable medical devices is being fueled by population health trends including the overall population aging, the prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, patient interest in self-management and controlling rising healthcare expense.

While the benefits, realized and potential, of these devices is apparent, they can only be achieved if they are used following physician’s instructions.

A device able to track heart arrhythmia is as different from an ordinary fitness tracker in design as it is in function. Those designs by necessity often mean the device is in greater contact with the user’s body than the wristwatch-like design of a Fitbit or Apple Watch. That contact can be uncomfortable for some users, leading them to use it only sporadically, defeating the purpose of long-term monitoring.

In particular, adhesives have drawn complaints from users, not only for the discomfort they cause, but because, according to an article on Healthcare Analytics News, “on-skin devices were not breathable, posing a safety risk to humans.”

Historically, many of the devices were made from “a form of polyester or rubber sheets, which get good readings, but don’t allow enough air to pass through,” according to a New York Times article. The lack of air inhibits sweating and causes irritations such as redness and itching.

Diagnostic heart and sleep monitors and therapeutic insulin pumps are examples of skin-adhered medical devices that struggle with user comfort. Devices that are uncomfortable, irritating to the skin, or difficult or painful to remove may cause the patient to use the device incorrectly – or not at all.

A new type of adhesive eliminates some of these drawbacks, according to the Japanese researchers who developed it.

The adhesive is described in the journal Nature Nanotechnology as an “ultrathin, lightweight and stretchable sensors. The Times article went one step further, describing the breathable sensor as “constructed from nanoscale mesh, a spaghetti-like entanglement of fibers a thousand times thinner than a human hair.”

The new sensor is designed to monitor vital signals over a long period of time, without the inflammation or skin irritation that often comes as a side effect of current devices.

The material conforms to the body’s contours while remaining attached and permeable. It’s also durable, researchers say, citing a test in which the device attached to a finger was still intact after 10,000 bends.

Resembling a temporary tattoo, this wearable affixes to the skin similarly, with a bit of water.

One drawback, however, is that it can also be rubbed off with water, meaning it will need to be replaced following the wearer’s bath or shower, according to the Times.

But the benefits of improved wearables are as great as their potential. Promising use cases include being used to monitor vital signals of pregnant women or patients undergoing physical rehabilitation at home or capturing muscle signals that can be used to control prosthetics.